MY TAKE ON THE 2023 OAKLAND TEACHERS’ STRIKE

What was the strike about, and was it necessary to reach an agreement?

On Monday, May 15, 2023, OEA signed a Tentative Agreement (TA) with Oakland Unified for a historic raise, and ended their seven-day strike.

The agreement included a 10% raise for all members, and $5,000 in one-time payments, plus a restructuring of the salary schedule for classroom teachers and some other positions that means the average raise was more like 15%.

That new structure also means that going forward, teachers will get a step increase in their salary every year until they reach the top level—unlike the current structure which leaves teachers in ‘frozen zones’ for years at a time, motivating them to leave for other districts instead.

As good as this deal is, it is very similar to the offer the district put on the table on May 1 in outline form three days before the strike started, and in specific language on May 3 on the eve of the strike. So if the offer was so good, why did OEA go out on strike?

There were two narratives justifying the strike, which did not fit with each other. The first one, that was mostly used before the strike started, said that the district was not bargaining seriously (allegedly canceling two bargaining sessions and showing up late to others), and so the two sides were so far apart that the only way the union could get a valid offer from the district was to go out on strike.

You can see all the proposals submitted by each side, with dates, and judge for yourself if they were seriously bargaining or not, on OEA’s own website. As you know if you have followed public sector bargaining anywhere in California, settling a major contract like this in under seven months is actually a relatively fast pace.

The second narrative, which emerged after the strike started and was very different from the first, was that the two sides were very, very close on compensation issues, but that the goal of the strike was to get the school board to authorize bargaining on five Common Good issues: school closures, reparations for Black students, housing/transportation, environmental justice, and community schools.

During the seven day strike, the school board never met to change its direction to staff not to bargain on these topics, and so in the end the union accepted essentially the deal that had been on the table before the strike began.

Instead of bargaining on the Common Good, the district signed Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) that were agreed upon at a table separate from the bargaining table. None of these MOUs had particularly strong language, and any of them could easily have been agreed to without recourse to a strike.

Many times during the strike, I was asked, why not just give in and allow the union and the district to simply discuss these Common Good issues?

Well, of course, they were discussing them, at the table where the MOUs were agreed to, and the district had expressed a willingness to work on MOUs on any of the issues long before the strike—but they were not bargaining over them, which is an important distinction.

If you have ever participated in collective bargaining, you know that it is a legalistic process that is nothing like a friendly discussion. (I was briefly a member of an OEA bargaining subcommittee in 2010, so I experienced it from the union side.) And one of the consequences of bargaining those issues could be future strikes on any of them.

But bargaining versus discussing was apparently an important enough distinction for the union to call a seven-day strike over. Why?

There are two answers to this question. The first is that you believe that Oakland Unified and our school board are so opposed to making progress on these issues that the only way to move forward is to win the right to strike over them.

I feel differently, because I believe that while the Common Good topics are challenging problems that are hard to make progress on, the Board is on the same side as labor on them most of the time, and the actual enemy are the structures of capitalism that keep funding for education and broader social change too low both in California and across the country.

I say this as someone who has fought for progressive change my whole life. I'm not going to try to prove my credentials here, but there is a reason I was endorsed by the County Labor Council and all the unions including OEA as a candidate in 2020. While my interactions with OEA leadership have been fraught since I joined the board during the pandemic, I have good relationships with the other unions in OUSD and am generally seen as a reasonable, progressive board member.

So that brings us to another possible answer to the question of why not bargain the Common Good: putting these issues in the contract would privilege OEA over other participants in our district (other labor unions, parents and students) who might not always be 100% aligned with OEA.

Throughout the strike, since the Board did not meet, Oakland Unified held firm that we should keep these controversies at our Board meetings, but not allow them to become a regular basis for future strikes that could shutter our schools again and again.

I understand that many people believe that the teachers’ union represents the whole community, and that therefore anything they are willing to go out on strike for must necessarily be worth implementing.

So let’s take a closer look at the specific Common Good issue that precipitated the strike, and whether OEA’s proposed language on that issue actually represented the will of Oakland at large.

On May 3, the one Common Good topic that union leadership insisted had to be in the contract was the Community Schools language. At that point, they had already acknowledged that the other issues could be addressed by MOUs, but on the eve of the strike, the sticking point was specifically Community Schools.

When the OUSD team gave OEA leadership a proposal late that evening that did not include the Community Schools language, they refused to even let the negotiator into the room with the bargaining team to present it, with the result that she had to send it by email instead later that night. The next morning, the strike began.

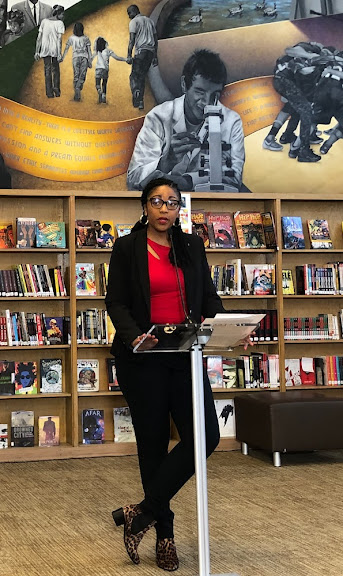

On the eve of the strike, Oakland Unified held a massive

district-wide science fair at Oakland High

with hundreds of students and their families.

These are the kind of culminating events that had to be

suspended or canceled during the 7-day strike.

Knowing what I know about the origins of that language, and how out of sync it is with Oakland’s history of implementing Community Schools, that seemed a strange basis for going out on strike.

I didn't expect that union leadership would follow through on striking solely for that reason, nor that the strike would go on for seven days once it began. And yet that’s what happened.

I am going to go into excruciating detail on this issue now, before given some broader thoughts further below. But the larger question to keep in mind is whether OEA’s position on issues necessarily represents the community at large, or whether there are competing interests at times between different labor groups, as well as other groups such as parents and students, and how to make sure that everybody’s perspective is represented.

All the adults, including myself, feel that they have the best interests of our students at heart, and that their strategy is the one that will be most impactful for helping them succeed and reducing the equity gaps for low-income students of color.

The question is whether the strategies that are chosen represent particular groups or are developed with input from everybody in the community.

Community Schools and School Site Councils

When the first round of California Community Schools Partnership Program grants were announced last year, more Oakland schools received them by far than any other district in the state.

This was thanks to Oakland Unified’s deep history creating and sustaining community school programs, where school communities develop their own vision of how to bring together partner organizations and services to offer wraparound support to students and families.

One of the conditions from the state Department of Education for the Community School grants is that schools must spend the money according to “priorities as determined by the community school leadership team(s) (a collaborative body of educators, administrators, families, students, community and civic partners)" (see p. 14 of the CDE’s RFA).

However, across the state, the California Teachers Association (CTA) has developed a strategy of using collective bargaining as an opportunity to put Community School language into teacher union contracts.

Community School implementation grant on May 19

The model language they suggest on their website gives the teachers’ union 50% of the seats on the district-wide decision-making body, and the district the other 50%. This language excludes unions that represent classified workers, as well as parent and student groups, from this committee.

This 50-50 split on the committee between teacher unions and districts has been included in contracts in districts like West Contra Costa (p. 71) and Montebello (p. 7).

The CTA model language also specifies the creation of a Community School Coordinator position that is a member of the teachers’ union. This echoes language from the 2019 United Teachers of Los Angeles (UTLA) contract (p.394) that “Each school designated for a Community Schools transformation shall be required to utilize part of the District 2019-20 and 2020-21 funding allocations to hire a Community Schools Coordinator. The Community Schools Coordinator position shall be recognized as part of the certificated bargaining unit represented by United Teachers of Los Angeles.”

While it is important that every community school has somebody in the role of coordinating services and communication, it is not necessarily in everybody’s interests that they be a member of the teachers’ union.

First, as one principal recently told me, that means this position would be subject to seniority rules that could cause Community School Coordinators to be bumped from one campus to another from one year to the next, instead of being committed to a specific school.

Second, since we are in the middle of a teacher shortage, requiring a teaching credential for this role would mean that many other classroom positions may sit vacant, leaving students with a series of subs, as too many of us have experienced as OUSD parents.

Third, it violates the principle of Community Schools that each school community gets to decide how to use the grant funding, because a districtwide labor contract will instead impose a particular use as a requirement.

In Oakland, we have long had Community School Managers (CSMs) at each of our community schools, but they are members of the United Administrators of Oakland Schools (UAOS) union, not OEA. As such, they do not go through bumping when there are layoffs, nor are they required to have a teaching credential.

On May 13, the Custodial Services department held its annual

Equity For All scholarship award ceremony, granting thousands of dollars to

students of all ages from TK to high school seniors.

OEA’s December 14, 2022, Common Good proposal specified that "OUSD will create the Community School Coordinator position (phase out CSM) which is a part of the OEA bargaining unit and allow current CSMs to become OEA members” (p. 3).

It also echoed CTA model language in proposing that grant decisions at each site would be made by a committee created jointly by OEA and administration, and nobody else. Those two parties would have chosen between them who would represent parents, students, and community.

This is a jarring idea in Oakland, where board policy and local practice has long been that School Site Councils or SSCs (where as the state specifies, parents select the parent reps, students select the student reps, and classified workers select the classified reps) are the school governance team.

On May 1, OEA presented a revised proposal, in which the Community School Teacher on Special Assignment (TSA) position would be in addition to the CSM, not supplanting them. The new language also revised the school-level decision-making team so that representatives would be selected by their own constituency, but it still seemed that this team would be a somewhat different body from the SSC.

During the strike, I posted on social media my belief that Community School funds should not be required to be used to pay for both a CSM and a TSA. For most schools, the grant funding is about $250,000 per year, and those two positions would eat up almost all of that money, leaving nothing left for the SSC to decide about.

I don’t know if my post influenced things or not, but shortly after that, the Community School TSA language disappeared from the OEA proposal, and the final MOU that OEA signed focused on the makeup of the district-wide steering committee. The MOU also specified that SSCs, not some other committee, will make site-level decisions. Both of these were provisions that I would have enthusiastically supported passing at the school board any day of the week.

Principal Nidya Baez presents an Equity for All scholarship,

along with Roland Broach, head of Custodial Services,

to a Fremont High student on May 13.

Given that OEA had shown a willingness to strike over very little, and also that their position on Community Schools had come from language from outside of Oakland that was not reflective of Oakland’s experience, nor respectful of other groups and perspectives with important interests at stake, I was firm in my stance that Oakland Unified should not include the Community Schools language as part of the bargaining.

If we had, that would make OEA the most influential voice on the Community Schools issue not only right now, but also set a precedent for future rounds of bargaining. And this whole story demonstrates that at times, OEA is prioritizing CTA and OEA’s interests over those of Oakland as a whole.

I could go into this level of detail on other Common Good issues as well, but I chose to focus on this one, since it was the main driver of the strike.

My Personal Experience

During the strike, every time I checked in with the negotiating team, I would hear that the two sides were extremely close, and that OUSD's team didn’t see a reason why a tentative agreement couldn’t be reached imminently. So every night, I would go to bed expecting to hear in the morning that there was a deal, only to be disappointed when I woke up and saw no happy messages.

Meanwhile, every day of the strike, two or three or four people would reach out to me at OEA’s request—other elected officials, labor leaders, or community members that had relationships with OEA and with me.

Those conversations would each go about the same. They would start asking if it was really true that both sides were very close on compensation, so the strike was truly not about that? (Yes.)

Then they would say that from their experience in the community, they knew it was hard to make progress on controversial issues like the Common Good demands, but that other districts like West Contra Costa and LAUSD had included Common Good demands in their teacher union contracts. (Yes, but I can’t speak for LA or West Contra).

Then they would ask me why not bargain on the Common Good. I would explain, slowly and reasonably, that five of our six board members were elected with labor backing, and we are all pretty aligned with labor on the bigger Common Good goals. So there is no need to bargain those issues or make them the basis of future strikes, since we can resolve those arguments in the Board meetings.

For some, that was enough, while for others I would go into the detail I have given above about Community Schools. For 90% of the conversations, the person would end by saying that I sounded reasonable and that they knew contract negotiations are rough, and being a school board member isn’t easy, so hang in there!

So the conversations had the opposite impact of what was intended—they convinced me that most community leaders understood my position. On Wednesday, OEA held a press conference outside City Hall, and invited many elected officials from outside of the Board of Education to stand with them in support of the strike. Only one showed up.

Meanwhile, many other parents, including neighbors and a local PTA president, were contacting me saying they thought the strike was unnecessary, and that they were scared to say anything to their teachers, but that they supported my position.

Still, the strike dragged on. Later on Wednesday, it became clear to me that my usual reasonable voice wasn’t working. Maybe they thought that if they kept sending person after person to talk to me, eventually I would give in.

I also heard that an OEA demonstration would happen on Thursday outside President Hutchinson’s house. Meanwhile, school board members in West Contra Costa, where Vice President Thompson is a teacher, interrupted his classroom lessons to talk to him about the strike.

and I went to Sacramento to lobby lawmakers on behalf of Oakland Unified.

So on Thursday, I dropped the reasonable tone and called a couple of friends of OEA to tell them angrily to stop sending people to try to change my mind.

I told them that I welcomed them to come demonstrate outside my house. If they did, the media would come and I would be glad to introduce them to Sankofa families of color in my neighborhood, who could tell them that they don’t see OEA as the champions of racial equity at their school that they claim to be.

On Friday, I noticed that no such demonstration arrived.

Around the same time, reportedly several Oakland community leaders reached out to OEA and told them that it was time to end the strike. On Saturday, after the Common Good MOUs were signed, the district presented OEA with its last, best and final offer, which was substantially the same as the offer before the strike on May 3. Finally, early Monday morning, OEA signed a tentative agreement and ended the strike.

The End

In summary, a generally pro-labor Board naturally put as much money as we could on the bargaining table, but OEA went out on strike anyway.

Their chief demand was the right to strike on hot-button Common Good issues in the future. Since I don’t believe that OEA alone represents the whole community, or even all of organized labor, on those issues, I was a hard no on that idea.

And so after seven days, they settled for the same historic raises that had been on the table before the strike, and signed the same Common Good MOUs that they could have gotten from the Board at any time.

at McClymonds High School announcing the Tentative Agreement.

What’s Next?

In the long run, how do we move forward? How do we re-establish trust between labor and management in Oakland Unified?

One step is for this story to be told. During the strike, I had so many conversations with friends of labor or other union leaders who felt the strike was a mistake, but were not willing to say so publicly. By getting this story out there, I hope that more of these conversations will happen where people will acknowledge that despite our community’s love of labor, there are times when union leaders also need to be held accountable for the decisions that they have made.

Second, we need to continue to do good work, including by working with people that we have had differences with in the past. A week before the strike, at the request of OEA leadership, I submitted an amendment to Board Policy 7351 on Housing, co-sponsored by Director Brouhard.

I see this new position from OEA, supporting affordable housing for homeless families and OUSD employees on vacant district property, as a very positive development, and I look forward to continuing to work with them on that. I expect that my Board Policy language will come before the board soon, and I am open to any further amendments that should be made to it.

Finally, over the past month, one of the narratives on Common Good was that Oakland can’t trust the District or the Board to make change on its own.

I ran for the board in 2020 because I was hopeful that labor-backed candidates could work together on progressive policies that would reduce the drama that always besets Oakland.

That drama has been severe over the twenty years since the district went into fiscal receivership, during which we saw many years of fiscal mismanagement and pro-charter leadership.

And the Board has achieved many things since I was elected:

The Oakland Unified enrollment system no longer includes charter schools on its website.

The Central Office is moving out of 1000 Broadway this month as the lease will fully end this summer.

I led the campaign to renew the popular College and Career for All initiative with Measure H, which voters approved with an overwhelming 82% yes vote.

We denied the only charter expansion to come before the board.

We maintained Oakland Unified’s commitment to ethnic studies and to dismantling the district’s police force, issues on which I am to the left of my predecessor in District 1.

Oakland was recognized as handling the pandemic better than most other large districts, offering regular COVID testing, N95 masks, and vaccines to all students, and supporting the Oakland Undivided initiative to provide laptops and internet to all families.

Instead of being sold to private interests or turned into charter schools, vacant OUSD properties are being dedicated to early childhood education, a future library, adult education and community services, and workforce housing.

Each of these issues has its own controversy—it’s Oakland, and we have strong opinions! Yet I hoped that with this kind of progress, the temperature in Oakland Unified was going to cool off a bit.

Instead it seems to have only gotten hotter. Still, I stay committed to the good work, and hope that with time, with the very big salary increases that we all have now collectively won for OEA members, and with the progressive victories I have just described, we will now see the mood finally start to shift in the right direction.

at the Paramount theater took place on May 23.

Thankfully the strike ended before graduation ceremonies began,

but at many high schools like Oakland Tech, seniors missed

their last days of class with their teachers and each other.

Thank you for the detailed discussion of this. It was a very difficult week for so many of us including those like me who have kids at OUSD.

ReplyDeleteFrom a parent perspective, it felt like there was a bit of a bait and switch going on. I hadn't heard anything about the Common Good items until the strike began and then it clearly became a big focus of bargaining. As someone who has a union job and has seen several contract negotiations and been on strike at my own job, I was surprised at the inclusion of the Common Good items in the negotiations. Contracts are generally about very specific details like time off and pay, those items seemed more like ideas and seemed out of place in a contract and it didn't seem like something that would be enforceable. Over time, the language got more specific, but I felt that there was still no way for those items to make their way onto a contract that would be enforceable. I was prepared for school to be over for the rest of the year.

But then when things turned around, I was frustrated that the union tried to present it as if they won on the Common Good items by putting them in the MOU. Essentially they just agreed to not put it in the contract yet they made it look like a victory and honestly I think most people took them at their word.

It started to become apparent to me during the pandemic that there were some outliers in the OEA leadership whose goals might interfere with my kids' learning. I thought once schools were open again we could trust them to stay open. My kids just started in OUSD in the fall of 2021 and already we've seen schools close twice for strikes. In my mind, I'm trying to prepare myself for the likelihood that this will happen again in 4-5 years unless something changes. I understand that OUSD has a really hard job and that they are not given the resources needed to do this job. I love my kids' school and their teachers are as good if not better than teachers you could find at any school in the state (public or private). But I really do want the focus on schools to be learning/teaching and not the other goals.

Ultimately, there was so much lost in this strike. It's really staggering - the pay the teachers went without during the strike, the money the district lost, the money parents had to pay to stay home from work or were lucky enough to get a much coveted spot at a camp, not to mention the kids sent to less than ideal situations for care. And ultimately, the strike really put a lot of stress on the community and the parents. I heard second hand that some families at Chabot who got a lottery spot there no longer feel safe at Chabot and are planning on transferring to other schools even though their kids are going to miss out on the opportunities that going to Chabot provides. This was a result of the strife the strike caused among the families. So it's really disappointing to see you confirm in this post all the things I suspected and see that OEA really didn't accomplish anything with the strike, but so much was lost. What can be done to make sure this doesn't happen next time?